Burning the Midnight Oil for Living Energy Independence

Programming Note: I recently received for review a copy of Waiting on a Train by James McCommons, published by Chelsea Green Publishing. I'll likely be talking about it next week, but til then, you can read James Kunstler's Intro online at AlterNet.

Back in early September, I discussed the Steel Interstate in the context of the Appalachian Hub. The concept of the Steel Interstate is electrifying main rail corridors and establishing 100mph Rapid Freight Rail paths.

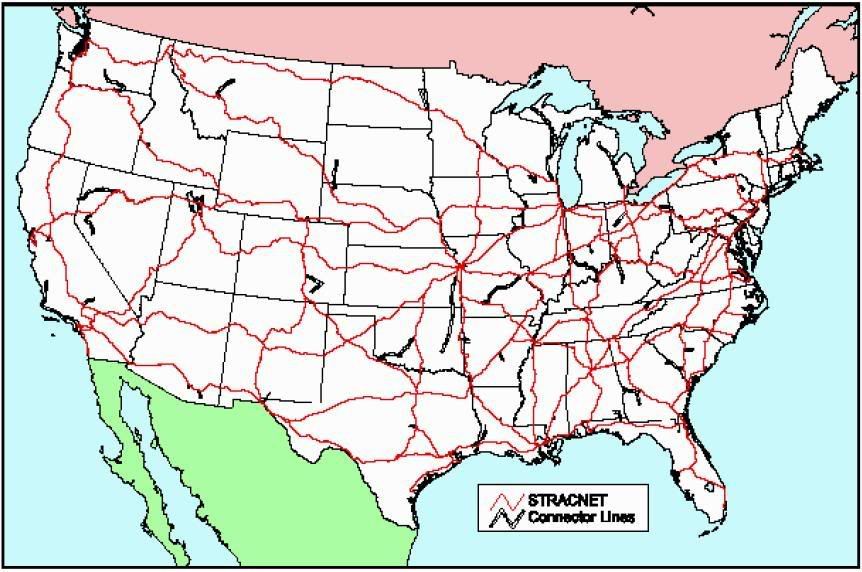

The broadest application of this concept is the proposal to Electrify STRACNET, the STrategic RAil Corridor NETwork.

The broadest application of this concept is the proposal to Electrify STRACNET, the STrategic RAil Corridor NETwork.The Appalachian Hub, recall, is a hypothetical Emerging/Regional HSR passenger rail network, modeled on the Midwest Hub and Ohio Hub plans.

And it is hypothetical, of course, because the state governments of the Appalachian regiona have been laying down on the job. The High Speed Rail corridor planning framework established under the Clinton Administration in the 90's is a bottom-up system, with states establishing High Speed Rail commissions, advancing plans to the stage of gaining designation as a HSR corridor, sorting out the financing, and applying for Federal funding.

This was almost entirely a "paper railroad" process during the eight years of the aggressively anti-railroad Bush administration. Of course, the low priority place on national security by the Bush Administration was most dramatically shown in its willingness to send US service men and women to fight and die overseas in pursuit of narrow partisan political advantage and the interests of the Oil Lobby ... but their aggressive anti-rail stance was yet another example of sacrificing US national security on the alter of the interests of the Oil Lobby.

In a a large sub-continental nation that imports 2/3 of the petroleum it consumes, the capacity to haul freight across the country by domestically generated electric energy is important for allowing our economy to cope with oil price shocks without collapsing into recession.

At the same time, its vital logistic support capacity for national security in the event of a serious disruption of a major oil export sea lane.

At the same time, its vital logistic support capacity for national security in the event of a serious disruption of a major oil export sea lane.And its not just the Bush family that sacrifices US national security so that it can pander to foreign and domestic oil interests ... its a trait of the modern Republican Party to use tough talk on US national security as a smoke cover for their policies which betray national security for thirty pieces of silver.

So the hypothetical Appalachian Hub includes Steel Interstates built on Electrification of STRACNET. But don't get the priority turned around - the electrification of STRACNET is a vital national priority, while the adoption of those corridors for the Appalachian Hub is an effort to leverage that foundation policy to gain additional benefit for the Appalachian region.

The Central Appalachian Hub

This is the context for the Appalachian Hub: the state-based system of HSR corridor planning has resulted in extensive plans backed up by ongoing incremental improvements in the Northeast, Great Lakes and eastern Midwest, and the Atlantic Coast down to North Carolina.

This is the context for the Appalachian Hub: the state-based system of HSR corridor planning has resulted in extensive plans backed up by ongoing incremental improvements in the Northeast, Great Lakes and eastern Midwest, and the Atlantic Coast down to North Carolina.In the area south and east of South Carolina, there is some notional planning for extending the Southeast Corridor to Florida and for a Gulf Coast corridor - but not backed up by the same state level support as elsewhere in the Eastern US. And in West Virgina, Kentucky and Tennessee, not even that much.

In that context, I sketched in two Steel Interstate corridors, to be used as the backbone of an Appalachian Hub. This first is the Steel Interstate proposed by Roanoke-based RAIL Solution from Harrisburg, PA to Knoxville, TN, extended along the STRACNET corridor from Knoxville through Chattanooga, Nashville and on to Memphis. The second cuts across Tennessee and Kentucky, following the STRACNET corridor from Cincinnati through Louisville, Nashville, and Chattanooga to Altlanta - and connecting into the Midwest and Ohio Hubs at the north and the Southeast and Gulf corridors in the South.

So, there's the backbone in Kentucky and Tennessee (note in the figure that an off-STRACNET Louisville-Indianapolis option is included, as a more direct Nashville/Chicago route) ...

So, there's the backbone in Kentucky and Tennessee (note in the figure that an off-STRACNET Louisville-Indianapolis option is included, as a more direct Nashville/Chicago route) ...... and I have previously looked at the more northern part of the Appalachian region in West Virginia and Pennsylvania ...

... but when looking at the STRACNET map, there is a part of Southern Appalachia that looks like it should be far more than just a stop along the way for the Gulf Coast corridor.

The Birmingham Hub

Birmingham, Alabama is one of the clearest hubs in the STRACNET system. In addition to the corridors to Atlanta and New Orleans in the Gulf Coast Corridor, there are STRACNET corridors to Pensacola, Chattanooga, Nashville, and Memphis.

So that's what I am adding here. Note that the STRACNET corridors to Nashville and Memphis are not that far apart in Northern Alabama, so that an alternative Memphis alignment option is noted that runs from the STRACNET corridor at Decatur, Alabama to the STRACNET corridor at Florence, Alabama.

So that's what I am adding here. Note that the STRACNET corridors to Nashville and Memphis are not that far apart in Northern Alabama, so that an alternative Memphis alignment option is noted that runs from the STRACNET corridor at Decatur, Alabama to the STRACNET corridor at Florence, Alabama.It is, of course, no accident that Birmingham occupies the place that it does in STRACNET. Nor is it pure political pork landed by some long-serving Alabama Senator or House Committee Chair. It is, rather, simple geography: when looking at the lay of the land in Southern Appalachia, Birmingham is located in a major valley between the Appalachian ranges to the east and foothills running off to the west.

This is a view of the Birmingham Hub lines as they run into Birmingham. It is, indeed, possible to organize the Hub into three corridors - Atlanta/Memphis, Chattanooga/New Orleans and Pensacola/Nashville. However, its not possible for all three to share a common transfer station in downtown Birmingham, since they converge on T-triangle to the east of the current Amtrak station, with Chattanooga and Atlanta on the eastern one leg, Nashville and Memphis on the northern leg, and Pensacola and New Orleans on the southern leg.

This is a view of the Birmingham Hub lines as they run into Birmingham. It is, indeed, possible to organize the Hub into three corridors - Atlanta/Memphis, Chattanooga/New Orleans and Pensacola/Nashville. However, its not possible for all three to share a common transfer station in downtown Birmingham, since they converge on T-triangle to the east of the current Amtrak station, with Chattanooga and Atlanta on the eastern one leg, Nashville and Memphis on the northern leg, and Pensacola and New Orleans on the southern leg.This offers an additional reason to run the Memphis route on the Nashville Corridor to Decatur and then run west to Florence. Then the Atlanta/Memphis corridor would have its own central Birmingham station, and transfer with the other two corridors at other locations: the outer suburban eastern Birmingham station to transfer with the Chattanooga/New Orleans corridor and the outer suburban northern Birmingham station to transfer with the Pensacola/Nashville corridor.

Financing the Birmingham Hub

The core of the financing of the Birmingham Hub is the financing of Steel Interstates. Construction of a State Interstate implies development of electrified Rapid Rail paths that support on-time freight delivery - whether by construction of dedicated Rapid Rail track or by construction of Rapid-Rail compatible track with time-slice allocation between Rapid Rail and Express Heavy Freight rail.

With the a Steel Interstate in place, establishment of Emerging/Regional Higher Speed Rail passenger services is a matter of building stations, where required, buying the trains, and hiring the staff. These trains will have higher revenue per mile than existing conventional Amtrak trains, lower staff costs per mile, due to the higher speed, and lower cost for traction per mile, as a result of electric traction.

Note that some operating subsidies may be required - just as the passenger aviation and passenger road systems require ongoing operating subsidies. However, if typical long distance Amtrak trains have operating recovery ratios of 40% to 50%, it seems a plausible goal for these corridors to reach 80% or higher operating recovery - and in the event of oil price shocks, which increase the need for operating subsidies for road and air transport, it seems likely that many of these corridors should generate operating surpluses.

Since freight rail already largely pays for the infrastructure it uses, unlike the air and road freight it competes against, and the Steel Interstate will reduce operating costs while improving its ability to compete, it is possible to leverage public investment in Steel Interstate projects by focusing on subsidizing interests costs while relying on user and access fees to refund the original capital costs.

In Sunday Train: Supporting Rail Electrification with the Climate Bill (11 October), I described a means of funding investments in Steel Interstates by allowing states to use part of their share of CO2 emission fees for subsidizing interest costs of building these systems. Additional sources of revenue could include:

- a per-mile user fee for long-haul trucks on the Interstate Highways, divided between State Highway Funds (to offset the inability of states to effectively tax the long haul trucks that rip up their roads) and a Steel Interstate fund

- a $5/barrel tax on imported petroleum, scaling down to $2 when the price of crude oil passes from $80/barrel to $120/barrel

- or, indeed, since this is a critical public investment with far more effective counter-inflationary impacts than the current standard counter-inflationary policy of running the economy in first gear to avoid people getting pay increases, an entitlement to a certain amount of Steel Interstate interest subsidy per capita could simply be appropriated.

Conclusions ...

The Appalachian Hub is an ongoing project, and so more critical than coming to any tentative conclusions at this point is to throw the floor open for discussion.

No comments:

Post a Comment